Using energy in homes causes 16% of United States greenhouse gas emissions1 and costs Americans $230 billion each year. About half of those emissions and costs come from heating and cooling homes.

We can reduce emissions and costs from heating and cooling in several familiar ways. We can keep our homes cooler in winter and warmer in summer. We can choose milder thermostat settings when we go to bed or leave home2. Homeowners can invest in insulation, air sealing, good windows, and efficient heating and cooling equipment. Governments can pass codes that make landlords to do the same.

But there’s another, less familiar way to reduce demand for heat and cooling: Living in dense housing.

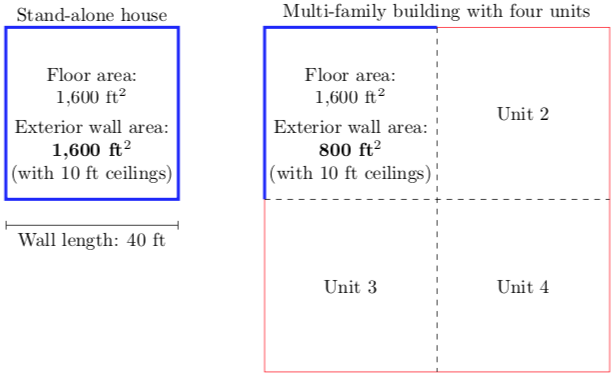

Homes in dense buildings (such as apartments, row houses, and condos) share walls with adjacent units, so have less wall area facing the outdoors. That means less heat lost to the outdoors and less heat needed from the furnace, boiler, or heat pump.

This “save energy by sharing surfaces” effect is why my cats used to get so snuggly on cold days. They lost no heat through whatever parts of their bodies they could get into contact with each other. Similarly, an apartment loses little heat through walls it shares with other units.

Sharing walls can save surprising amounts of energy. As the figure below shows, a stand-alone house has twice as much exterior wall area as a unit with the same floor area in a four-unit multi-family building. That means the multi-family unit needs about half the heat in winter and half the cooling in summer. Half the demand, half the emissions, half the costs.

Data from the Energy Information Administration’s Residential Energy Consumption Survey support this theory. On average over the United States, detached single-family houses use about 19 thousand BTU per square foot per year for space heating3. Apartments in buildings with five or more units use about 10 thousand BTU per square foot per year4. Half the demand, half the emissions, half the costs.

Cutting a house’s heat demand in half through renovations – such as insulating, air-sealing, and replacing windows and heating equipment – is very difficult. While energy-efficiency renovations of that depth are possible, they often take years and cost tens of thousands of dollars.

Dense homes can have other benefits. They tend to be in dense neighborhoods, where people can get to friends, food, and fun without driving. Driving less reduces emissions, fuel costs, traffic, and the number of people that car crashes injure or kill. Dense homes also tend to use space more effectively than stand-alone houses, letting residents live comfortably in less space. This can further reduce demand for heat and cooling.

- According to the EIA, residential and commercial buildings caused 29% of US greenhouse gas emissions in 2022, including indirect emissions due to electricity use. Buildings also used 40% of final energy (22% residential, 18% commercial). Allocating emissions between the residential and commercial sectors in proportion to their energy use gives a residential emissions estimate of 0.29*0.22/0.4 = 0.16, or 16%. ↩︎

- Shameless plug: My research group works on ways to automate thermostat adjustments to reduce demand for heat and cooling, improve equipment efficiency, and keep occupants comfortable. ↩︎

- The average US single-family home has 2,264 square feet of floor area and uses 44.0 million BTU per year for space heating. ↩︎

- The average US apartment in a building with five or more units has 905 square feet of floor area and uses 9.1 million BTU per year for space heating. ↩︎